|

New York News Publishers Association |

|||

Sunshine Week 2021 - March 14-20

Sunshine Week is a national initiative to promote dialogue about the importance of open government and freedom of information. Participants include news media, civic groups, libraries, nonprofits, schools and all others interested in the public’s right to know. Sunshine Week seeks to enlighten and empower people to play an active role in their government at all levels, and to give them access to information that makes their lives better and their communities stronger.

Click here to access a teaching guide including graphic organizers highlighting Freedom of Information & Sunshine Week.

Click on the image below to view a short video providing a basic summary of New York state's Freedom of Information Law (FOIL).

Click on the next image to view a short video that highlights New York State's Open Meetings Law.

As editorials and editorial cartoons become available, the content will be posted below. This content is available for all NYNPA member publications to reprint with attribution to increase public awareness of Sunshine Week and their right to know. Additional content will be added as it is received.

USA TODAY Network Atlantic Group Editorial Board

|

Don't use COVID as an excuse to hide truth from the publicFor more than a year, we have worked every day to bring New Yorkers the facts as our communities have faced wave after wave of pandemic grief. Accuracy is our first duty as journalists — and we reaffirm our devotion to the truth this week as we mark the 16th annual Sunshine Week, an annual effort by news organizations across the nation to promote transparency and open government. Over the course of the last year, as USA TODAY Network Atlantic Politics Editor Joseph Spector reported earlier, the pandemic has become a frequent shield against government transparency. In New York, we need look no further than Gov. Andrew Cuomo. Last April, he proclaimed himself as a champion of facts. "People are smart, if you give them the facts and they know, they trust the facts and they trust the person who is giving them the facts," Cuomo said. "They will do the right thing." A year on, Cuomo faces calls to resign amid sexual harassment allegations and his administration's murky disclosures on the number of New York nursing home patients who have died in the COVID-19 crisis. Cuomo didn't give the people all the facts, it turns out. As a consequence, the U.S. Justice Department is investigating the Cuomo administration's underrepresentation of nursing home deaths. That COVID has become a cloak for government that has shrouded ready access to data and public records is another remarkable consequence of this pandemic. Blair Horner, a longtime ally of the state's press corps and legislative director of the New York Public Interest Research, shares that lament. Horner said 2020 "was the worst year that I can remember for government openness. The pandemic was a convenient excuse to avoid public scrutiny, and it played out everywhere in New York." Indeed, public records requests made by USA TODAY Network New York journalists continue to languish:

State officials have explained the lack of transparency on releasing key COVID-19 data on the rapid crush of data being recorded to track the pandemic's reach. At the height of the crisis, New York was recording as many as 800 deaths a day. While some delays are understandable, a pattern of blaming the pandemic for a lack of transparency cannot and should not be tolerated. We call on our representatives in the Legislature — and at every level of government in New York — to work now to hasten and compel the speedy return of freedom of information requests related to COVID-19, as well as longstanding requests for all kinds of information from both the public and the press. We call on our readers to echo and amplify our call — here and now — for a new era of transparency and good government in the Empire State. |

Editorial Board

|

Lawmakers have opportunities to improve transparencyIn New York, progress on open government and transparency is usually measured in inches. This year, the state Legislature has an opportunity to take leaps with several key pieces of legislation that, if passed, would make it easier for citizens to get access to public records and learn more about their government. One issue with which we’ve had a particular problem over time that lawmakers may finally address is the portion of the state Freedom of Information Law that allows law enforcement to withhold records that are “compiled for law enforcement purposes and which, if disclosed, would interfere with law enforcement investigations or judicial proceedings.” Sounds reasonable, right? You don’t want to disrupt trials by disclosing confidential information. But district attorneys and police have exploited the word “compiled” to withhold any document used in an investigation, even documents that were already in the public domain and which would not normally fall under other exemptions. Back in 2017, for instance, the city of Schenectady used that provision of FOIL to deny public access to code enforcement documents related to the buildings involved in the March 2015 fatal fire on Jay Street, as well as access to email communications among city officials. The documents were once available to the public, but were snatched from the public record for the investigation into the blaze. Reporters and citizens have been similarly thwarted by the “compiled” exemption many times. A bill passed by the Assembly (A5470) clarifies that records cannot be withheld solely because they relate in some manner to an investigation or criminal proceeding. The bill also would ensure that when the law enforcement exemption is used to deny a FOIL request out of concern for the record’s potential impact on judicial proceedings, only the presiding judge can determine whether to release such information. That takes the decision out of the hands of government officials and prosecutors. The Senate needs to take up this bill and pass it. Another good bill (A3203A), the LLC Landlord Transparency Bill, would require the disclosure of names and residence addresses of members, managers or other authorized people of a Limited Liability Corporation in lease agreements where the state is the tenant in office buildings owned by the LLCs. The reason this is important is because often political contributions are funneled through LLCs, and that raises questions about whether lucrative leases are being awarded by state officials in exchange for those contributions. This bill would add more clarity to the law so that the public could more easily identify those connections and detect possible fraud or malfeasance. Another bill (A924/S1625) would help reduce the ability of governments to hide information. Many times, governments create non-governmental bodies that aren’t subject to transparency laws to skirt the FOIL and Open Meetings Law. This would expand the definition of a public body to include them. To help make sure state economic development money is being used appropriately, bill A2334 would force the state create a searchable database to allow citizens to review and monitor economic development programs for effective use of taxpayer dollars. To help citizens have better access to government meetings, bill A1228/S1150 requires government boards to post meeting documents online at least 24 hours prior to a meeting and sets new rules and timetables for live-streaming and posting videos of public meetings. These are just some of the ways lawmakers could make government more open and accessible. Contact your state assemblyman and senator’s offices and urge them to support these bills and other vital legislation for your right to know. |

Editorial Board

|

FOIL is a tool, but be prepared to follow upSo you’re interested in obtaining some records from your state or local government or school district, and you want to go about asking for them. For that, you need to first familiarize yourself with New York’s Freedom of Information Law, or FOIL. There are strict rules that governments must follow in deciding when or when not to release records, and there is a process for citizens to follow to request those records. For starters, the Freedom of Information Law is based on the presumption of access — if the government has a record, it’s assumed to be available as long as there are no legal restrictions against releasing the records. There are 11 reasons why a board can deny a record, most related to law enforcement, employee contract talks, legal strategy and disclosure that would create an “unwarranted invasion of privacy.” If the record doesn’t fall under one of those exemptions, it must be released.

Governments will try all kinds of word tricks to deny citizens access to records. A common one is that the information might be embarrassing or make someone look bad. That is not a legitimate excuse for withholding a record. Governments will also try to mark records as “classified” or “confidential.” That’s an indication that they’re hiding information they don’t want to release. Just because they mark something confidential doesn’t mean that it can be withheld. Make sure the records truly fit one of the exemptions. They’ll also try to hide a record on the basis of possible litigation. That’s not a term in the Freedom of Information Law. Hold them to the exact language of the law. So you identify the record you want and you now want to request it. We suggest first contacting or visiting the records officer, usually with the word “clerk” in their title, and ask first. Also, check online to see if the record is already posted. Some governments have taken to the practice of posting commonly requested records so save citizens and themselves the time and effort of requesting and responding to a FOIL request. If a board asks you to file a formal FOIL request, don’t panic. Filing a FOIL is pretty easy. A template is available on the Committee on Open Government’s website. Just cut and paste that template into an email or letter and fill in the blanks for what information you’re requesting. Be as specific as possible, both to ensure you get the exact records you want and to either keep the government body from wasting its time tracking down unnecessary records or giving it an excuse to deny you a record. For instance, include a range of dates to narrow down the request. You can submit FOIL requests by email. Make sure you’ve got the right person, or your request could be lost or discarded. If you’re unsure, follow up with a phone call to make sure it got to the right person. Officials have to respond within five business days, telling you whether they’ve decided to grant your request, deny it, or tell you how long your request will take. Boards can charge for copying and work involved, so make your requests specific and ask for costs in advance. And be prepared to pay something if they require it. But filing the FOIL request may just be the first step. If a board denies your request, you will have to consider whether you want to file an appeal, giving a specific reason why the board’s denial was incorrect. If you still don’t get the record you want and you feel you’re still legally entitled to it, you may have to consider taking the government body to court, which could get time-consuming and expensive. Government bodies that want to keep secrets often rely on a citizen running out of time, money or patience to deny you access. So be aware that you could be in for a battle. Even if you go to court and a judge finds in your favor and awards you court costs, it still can be a lengthy and costly process. Before going to court, go directly to one of your elected officials, or contact the media. They sometimes can help draw attention to your plight and help you pry loose the records. For more information on state the Freedom of Information Law, the state Open Meetings Law and other helpful information, visit the state Committee on Open Government website at: https://www.dos.ny.gov/coog/. Good luck. Remember, it’s your right to know. Exercise it. |

Jeremy Boyer Executive Editor, The Citizen, Auburn, New York

|

Demand more sunshine from your governmentThe state Assembly's proceedings immediate halted Tuesday when the Democratic majority leadership learned that someone within their conference had leaked a recording of a recent private meeting. The response was to break off into another private discussion about the leak of the previous private discussion, which eventually became the subject of a story published by Yahoo News that night. And the result of it all was for Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie to declare an end to larger private group discussions, in an effort to prevent future leaks. The subject matter of that original meeting, of course, is far from a private matter. It's something that every New York state resident has a right to know about — the Legislature's handling of misconduct allegations against Gov. Andrew Cuomo. But yet on March 16, the date recognized in the United States as Freedom of Information Day, in part because it coincides with birthday of James Madison, the founding father who was a fierce advocate for open government, elected Democratic Assembly members were tearing each other apart over the desire to keep the public in the dark. Freedom of Information Day falls during an annual weeklong effort to bring attention to the importance of government transparency called Sunshine Week. That work continues through Saturday, March 20. We've always aimed to bring awareness to our readers about Sunshine Week, because it's important we all understand the fundamental relationship between access to public information and a healthy democracy. We also want them to understand the state and federal laws that protect citizens' right to know are there not just for journalists, but for anyone. You don't have to be a reporter to request public information from your government at any level, from the White House down to the village hall. You also don't have to be a reporter to express to your elected officials that you want them to improve transparency. Unfortunately, many politicians talk a good game when it comes to standing up for open meetings and access to records. They definitely do so every year during Sunshine Week. But the secret meetings and stonewalling are never going to stop unless we demand better. The same goes for proactive access to information at every level, especially in the internet age when so much information can be posted online. In New York state, there's been an unfortunate trend of governments requiring people to file formal Freedom of Information Law requests for some of the most basic information. While this law ultimately protects our right to get that information, it also establishes a legal clock that many governments use to delay disclosure. I've described examples of this practice in past columns. The state Department of Corrections and Community Services took more than two months in 2019 to tell us how long a parole violator's new sentence was. A request last fall for the number of residents and staff at a state-run juvenile detention facility is taking at least until spring for the Office of Children and Family Services to answer. We recently asked for the records associated with a health-care worker's license suspension that was referenced in a state Education Department press release, and it took more than a month to get the documents. All three of these examples relate to information that clearly belongs to the public, and it's information that the state's highly paid state communications officials could get back to us with a few keystrokes if they wanted to help. But instead they play a FOIL delay game as a routine practice now, and we all are left in the dark for too long as a result. One recommendation that open government advocates make at all levels of government that could effectively address this problem is proactive disclosure. Government agencies at all levels now have the ability to post digital records on their websites, and the more they do that, the less need there is for state and local employees to process FOIL requests. All three examples I mentioned — a parole board decision, a state facility's staff/resident census, an education department licensing suspension — could and should be online. So as another Sunshine Week comes and goes, my request to our elected officials is to push the governments they oversee in the direction of proactive disclosure. Doing so would demonstrate a true commitment to transparency. |

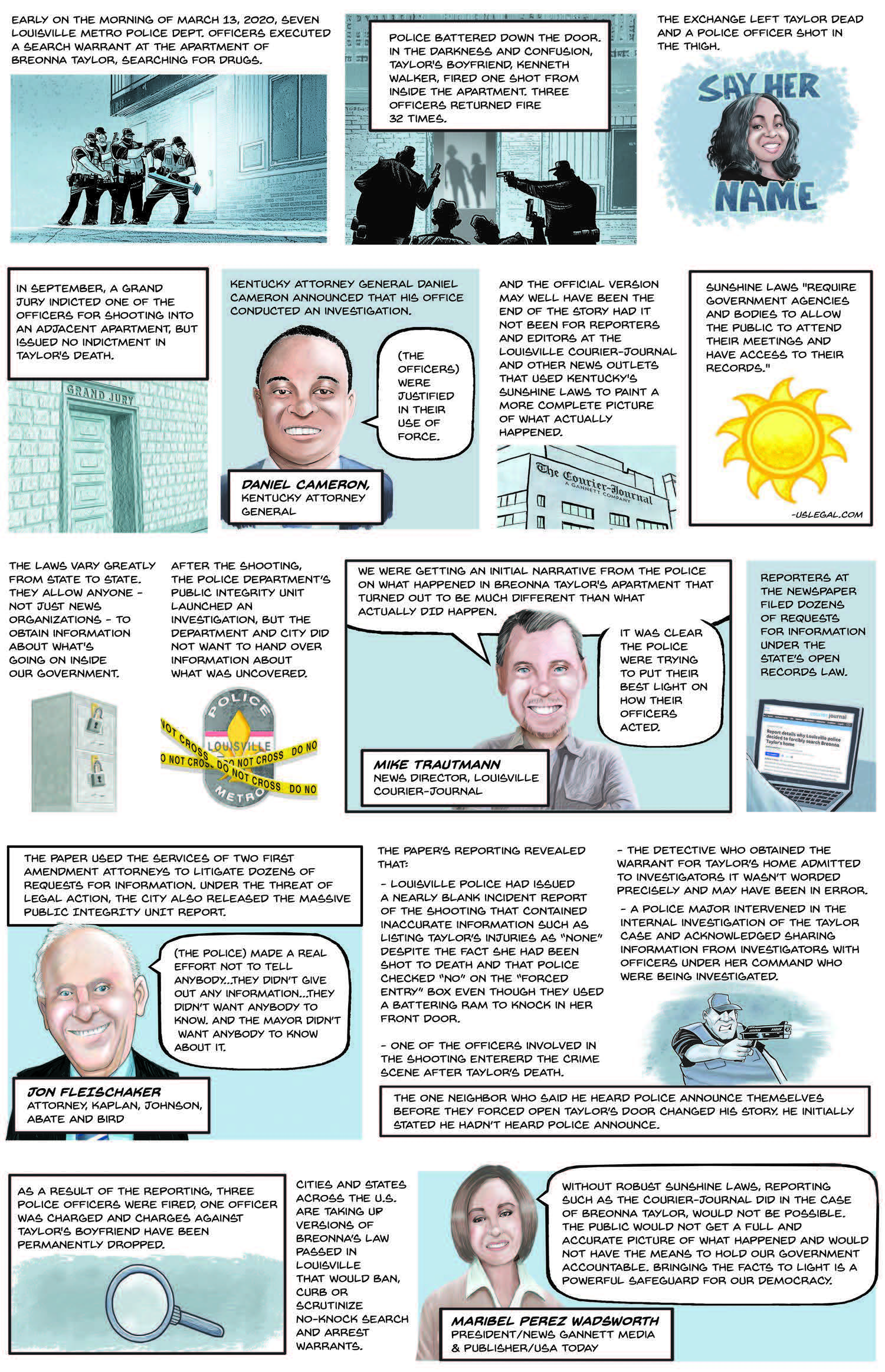

SUNSHINE WEEK OP-ED GRAPHIC NOVEL

Breonna Taylor killing highlights importance of Sunshine Laws

Story and art by MIKE THOMPSON

USA TODAY

Find the PDF of this graphic novel cartoon here.

Joseph Spector USA TODAY Network Atlantic Group Politics Editor

|

Why COVID-19 proved to be a bad year for openness in governmentLast April, Gov. Andrew Cuomo was a national star, and during an appearance on the Ellen DeGeneres show, he said the reason for his appeal was simple: He gave people the facts about COVID-19. "People are smart, if you give them the facts and they know, they trust the facts and they trust the person who is giving them the facts," Cuomo said. And with the facts, he continued, "They will do the right thing. And that's what the people in New York did, and I think that's what you have seen across the country." A year later, Cuomo is under siege for not revealing all the facts. His office is under investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice for underrepresenting the number of COVID deaths in nursing homes, only revealing the true number after a state Attorney General's report. The situation, which has led to calls for Cuomo to resign along with sexual harassment allegations against him, was the most significant example of how COVID shined a new light on the lack of transparency in government when it comes to releasing data and records in a timely manner, critics said. "This was the worst year that I can remember for government openness. The pandemic was a convenient excuse to avoid public scrutiny, and it played out everywhere in New York," said Blair Horner, legislative director for the New York Public Interest Research Group. The criticism comes in advance of Sunshine Week, which is the annual campaign in March to highlight open records laws. The effort was started by newspapers 16 years ago to promote transparency in government. And it's not just an issue in New York. Other states have been accused of also denying or delaying records requests under the guise of the pandemic. In neighboring New Jersey, Gov. Phil Murphy has been criticized for withholding key COVID details, such as how many health-care workers have gotten sick or died from COVID — data New York has also not made public. While New York in the 1970s became one of the first in the nation to have its own state Committee on Open Government to advocate for transparency, state and local governments are often criticized for not being forthcoming with records requests. Some requests to state agencies can languish for years. A recent example: The USA TODAY Network asked in November 2019 for basic data on state spending at airports. A year and half later, on March 5, a short list was provided. The examples can go on and on. A law last year that made police disciplinary records in New York public has also been a struggle to attain. One central New York police department said it would release its records, but the price tag? $47,504. MuckRock and the USA TODAY Network, which have partnered on a project regarding police discipline, filed more than 600 Freedom of Information requests last year for police records. By December, it had only gotten about 40 back. The police records aside, COVID was often used as a reason over the past year why many requests to state and local governments were delayed, often with the reason that agencies were overwhelmed responding to the pandemic. While in some cases it was true, the COVID crisis also made releasing data about the virus' spread critical. And the state was often knocked for not being as forthcoming as it could with the data, which could help guide policy decisions and where to direct resources to fight the spread. The state initially was knocked for not quickly releasing data on the demographics of those who got COVID and died from it. Then it was criticized for not being forthcoming with the number of nursing home deaths. State officials said it was simply a matter of a crush of data coming all at once and making sure anything released publicly was accurate. In the height of the pandemic, New York was dealing with as many as 800 deaths a day, by far the most in the nation. Certain delays can be understandable during the unchartered waters of the pandemic, Horner said. But a blanket policy of not being forthright with data and decisions is another problem. "It’s the strongest evidence of a pattern that existed pre-pandemic that was accelerated by the pandemic: the pattern of government secrecy," Horner said. For example, Cuomo was given broad powers to adjust state spending as the pandemic unfolded, and lawmakers often complained that decisions were cloaked in secrecy. Earlier this month, the state Legislature curtailed Cuomo's emergency COVID powers, in part because they wanted a larger say in the decision making. But fiscal watchdogs urged lawmakers and Cuomo's office too provide more details about any funding that was withheld from state and local agencies due to the state's fiscal crunch over the past year, saying a full accounting -- despite requests -- has yet to be fulfilled. "In summary, we ask that you provide transparency of the fiscal year 2021 withholdings and repayments by agency or recipient, and provide similar detail for the final proposed 5% spending reductions in the current year and permanent spending reductions in the out-years," the groups wrote in a letter Wednesday. There's another public information battle underway: Lawmakers want Cuomo to release details about the financial details of his COVID book released last fall, saying it might shed light on Cuomo's policy decisions. Cuomo has refused to do so, saying it will show up instead in his annual disclosure reports this summer. Lack of transparency over nursing home dataThe most egregious issue came in January, when Attorney General Letitia James released a report Jan. 28 that showed the state had not reported about 50% of the deaths in nursing homes as residents' death. Instead, New York had reported a much lower count of nursing home deaths because residents who died in hospitals weren't added to the nursing home death total. When the state released the full figures hours after James' report, it showed about 13,000 deaths associated with nursing homes in New York — which was still slightly less than the national average. Health Commissioner Howard Zucker said the data wasn't released simply because they couldn't be confident there wasn't a double counting of the deaths. But weeks later, Cuomo's office was accused of holding back the figures in a July report, even after Health Department officials recommended the data be included. Critics said it allowed Cuomo for months to tout a lower number of nursing home deaths than was actually the case. Even Cuomo admitted the state should have been more forthright with the data. "I understand that they were not answered quickly enough, and they should have been prioritized and those requests prioritized sooner. I believe that," Cuomo said Feb. 15. The problem, though, is the lack of immediate information made it hard for lawmakers and others to respond to where the virus was spreading, said Assemblyman Ron Kim, D-Queens, who has leading the criticism over nursing home deaths. "So if they had a say in hiding that data, meaning like separating the deaths from the hospitals and nursing homes, so that way we can lower the number, then every one of those people, including the governor, needs be help accountable because they took away our right to legislate," Kim told the USA TODAY Network last month. That's not all: Both the Associated Press and the Empire Center for State Policy successfully won in court to have more details released about nursing home deaths. In a Feb. 2 ruling, Supreme Court Judge Kimberly O'Connor knocked the Health Department for its delay in releasing the data to the Empire Center. She ruled that not making the information public "goes against FOIL's broad standard of open and transparent government and is a violation of the statute." The records were soon after released by the state. |

Gene Policinski Senior Fellow for the First Amendment at The Freedom Forum

|

You Can’t Have Democracy Without a Free PressThere’s a reason we need a free press, despite its faults and foibles: Democracy won’t work without it. The grand experiment in self-governance that is the United States is rooted in trust and confidence we all will work toward the greater good. But the nation’s founders had experience with a king and his expected benevolence — and what could happen when things didn’t work out. So, they provided for three branches of government to balance each other, along with periodic elections and the rights for us to assemble and seek change when we think things have gone astray. All fine, but also relatively long-term solutions. How do we know what our government is doing, how well it is operating or whether our elected officials are up to the job? Enter the only profession mentioned in the Constitution: A free press, to serve as a “watchdog on government.” A free press the government cannot control, to offer an independent, regular update on behalf of the rest of us. Let’s stop to acknowledge that many of us are dissatisfied with the free press we have. Survey after survey shows low public trust in our news outlets and in the journalists who staff them. But in those same Freedom Forum surveys about the First Amendment that began in 1997, the desire for that watchdog role remains high, often supported by a majority of people questioned. How can these two results co-exist? The answers rest in what kind of press we mean. Much of the highly visible kerfuffle on social sites today concerns national reporting, and more narrowly, the political pundits on cable TV and the tiny percentage of journalists who are the White House press corps. For most of us, today’s journalism is something different — and much more relevant to us. We see a news media bringing us the day-to-day information we need to live our lives: What local officials are saying, weather forecasts and crime, health and safety reports for our communities. The work of journalists helps us get things done. Reporters ask the questions we would ask if we could be there. Jurors in Des Moines, Iowa, this week appeared to support the role of journalists as watchdog when they acquitted reporter Andrea Sahouri, who was arrested while covering a Black Lives Matter protest despite her repeated protestations that she was a journalist. Local journalists, who are the vast majority of the 24,000-plus on the job today, live in the communities on which they report. In just the past month, they have reported on COVID-19 vaccination programs — both the successes and failures by officials we depend upon to keep us safe and fight the pandemic. Other recent stories told by big and small news operations alike will benefit hundreds of thousands, if not millions of us. A report on nursing homes in New York state disclosed they may have tested unproven COVID-19 treatments on residents, despite safety warnings, without telling family members. A news partnership in South Carolina found the state has dropped virtually all oversight of local officials’ activities, leading to “questionable or illegal perks of holding public office.” In Mississippi, residents now know a biodiesel plant is accused of illegally dumping hazardous material into public waterways. Throughout our nation’s history, it has been a free press that has probed, prodded and produced safer food and medicines and helped reveal waste, fraud and abuse of public trust. Reporters uncover these stories only by poring over records, reviewing court documents and interviewing sources — activities most of us don’t have the time, skill or opportunity to do. The guarantee that a press is free does not guarantee it will always be good or correct, or that we will like what it presents. But there are more ways than ever to get news and information and to find reports we can trust or verify. Ironically, the newest source for news and information has helped create some of the greatest threats to a free press in the nation’s history:

Not all the news about a free press is bleak. New financial models are being tested. Collaborations between news organizations and nonpartisan expert collectives have shown results. New attention is focused on regrowing the ranks of local journalism. But more is needed, from increased public support to new revenue sources to regaining the public trust. On March 16, we celebrate the birthday of James Madison, the principal author of the First Amendment and the rest of the Bill of Rights. He called a free press “one of the great bulwarks of liberty.” This generation, perhaps unlike any other, is being called on to defend that bulwark and, in the process, protect our liberty. |

Editorial Board

|

The light of scrutiny: Sunshine Week lauds efforts to ensure government transparencyThe right of constituents to access records that governmental bodies have collected as well as attend public meetings where vital issues are discussed remains an essential component in how we practice democracy. |

Mark Mahoney Editorial Page Editor,

|

Access to government is in all our interestsIt’s sometimes a challenge to get ordinary people fired up about open government and transparency. Admittedly, it can be perceived as a dry, legal-ish hobby for political junkies (like politicians and their staffs), government nerds (reporters and editors) and gadflies (an unflattering moniker for vociferous citizens who seem to raise their hands a lot at government meetings). So a bunch of people push papers back and forth and haggle over numbers on a ream of computer paper. The world goes on elsewhere. But for those who need to see fire before they check out the smell of smoke, the situation involving the state’s cover-up of nursing home deaths related to coronavirus was a five-alarm blaze. Short version: The state was hiding the real numbers relating to deaths in nursing homes during the crisis, particularly after getting criticism for an ill-advised policy to require nursing homes to accept discharged covid patients from hospitals. It turns out that not only did the state not want the numbers to get out, but that top officials in the governor’s office allegedly manipulated the figures downward to make the state and the governor look better in the public’s eyes. While many people sought the figures, it was only through the persistent pursuit of the information by a government watchdog group, the Empire Center for Public Policy, that finally convinced a court to order the state to release the figures to the citizens. It took months of them filing Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) requests, having those requests denied, filing appeals and publicly demanding accountability. The effort took time, money and a dogged commitment to informing the public. The result of that effort was that the public and state lawmakers finally got a better picture of how the state handled the nursing home situation and of the true impact of state nursing home policies. The governor’s office’s blatant attempt to hide the nursing home information and the effort by the Empire Center, the media and others to get that information released contributed in no small way to least a dozen pieces of new legislation designed to improve conditions at nursing homes and to make it easier for the public to learn what’s going on inside them. Score one for the nerds. This situation is just one example of how far government will go to withhold information from the citizens, and an example of the kind of effort often needed to pry that information loose. A few years ago, local officials went to great lengths to withhold vital information about a March 2015 fatal fire on Jay Street in Schenectady, using a poorly worded loophole in the state Freedom of Information Law to withhold and delay the release of public documents about building inspections and the condition of the buildings involved. For many years, police agencies have been withholding information about police misconduct, particularly the disciplinary records of officers accused of abusing suspects, and about lax police department disciplinary policies. The release of such information could protect the public by forcing rogue officers from their jobs before they can injure or kill another citizen during an arrest. But even after the state passed a law in the midst of the George Floyd death requiring that information be released, police departments are still fighting in court against the release of these types of records. Not all requests for public information, of course, are life-and-death. Most are more mundane. But that doesn’t mean they’re not important. The Freedom of Information Law is used by reporters, watchdog groups and the general public every day to uncover conflicts of interest among government officials and the individuals and businesses with which they have dealings. Filing FOIL requests is the only way we the people might learn about why a school official suddenly resigned, why a particular community spent money on legal assistance, or how much of our tax money is being used to compensate a particular government employee. One of our reports right now is juggling three separate situations in which government bodies are fighting the release of public records. That reporter is one of many engaged in the same type of battle with government. In theory, access to public documents is presumptive: If a record is not specifically prohibited by law from being released, it should be released. But in reality, government officials who don’t want the public to know about their activities work actively every day to control and limit the flow of information to the citizens. They’re abetted by inadequate state transparency laws that make it difficult, time-consuming and potentially costly for the public to obtain records they’re entitled to see. There have been improvements in recent years to the laws, particularly in forcing government bodies to pay court costs when they blatantly violate the law to keep information secret. Loosening the police unions’ grip on disciplinary records was a big victory for the citizens’ right to know, although that battle is still being waged. And some vigilant lawmakers are still pushing for laws (which we’ll go into detail about later this week) to expand the public’s access to government records. But in all, the fight for government transparency is a never-ending, uphill battle. Each year around this time, the media takes a week to shine attention on the fight for open government. It’s called Sunshine Week, the name being a metaphor for the effort to shine a bright light on government secrecy. Throughout the week, we’ll publish editorials on pending legislation, draw attention to issues related to transparency, and give citizens some tools they can use to help themselves become more informed and aware. Don’t confuse dry, boring and legal-ish with unimportant. When it comes to what government activity, we all have an interest in transparency. |

Ken Paulson Director of the Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University, a lawyer and a former editor-in-chief of USA Today

|

Open government is key to honest governmentWhen government fails, it’s the rare public official who says, “Oops. My fault.” That’s human nature, particularly for officials in the public eye who may have to run for office again. No one wants to be held directly responsible for letting the public down. Case in point is the recent catastrophe in Texas, when unexpected winter storms left 4 million homes without power, ruptured pipes and tainted the water supply for many. Texas’ energy grid essentially collapsed. While Texas Gov. Greg Abbott was quick to blame frozen wind turbines, the cause was much more complex than that. To truly understand how things went so terribly wrong will require time, study and research. So, too, with the coronavirus vaccine distribution. In this state and others, residents are frustrated with the slow rollout of vaccines. Is it poor distribution? Politics? A flawed strategy? These are literally matters of life and death. But how do you get to the truth when public officials so rarely step up to take direct responsibility for failures? The need to fight for government transparency is reaffirmed each year during Sunshine Week, a national awareness event overseen by the News Leaders Association and keyed to the March 16 birthday of James Madison. The fourth president of the United States drafted the Bill of Rights – including the guarantee of a free press – in 1791. That journalism connection reflects the role news media play in the free flow of information, but it unfortunately can also leave the public with a sense that Sunshine Week reflects the concerns of a single industry. To the contrary, access to government information is critical to every American who cares about the quality of his or her community, state and nation. It’s important to see government employees – including elected officials – as the people we hire through our tax dollars to do a good job for all of us. If you run a business or hire a contractor, you wouldn’t hesitate to demand a full understanding of how something went wrong. That should be exactly our relationship with government. Getting that information, though, requires public meetings where residents can ask questions. It also means access to the documents that led to a poor decision. Words on paper can be much more forthright than the dissembling of politicians. It’s critical that we hold government accountable, for better or worse. (It’s also important to acknowledge when government leaders are doing a good job.) First, keep doing exactly what you’re doing at this moment. Read and support your local newspaper. Local journalists, more than anyone else, will stand up for your right to information. Facebook will not be going toe-to-toe with your mayor. Second, when you believe government isn’t doing its job, demand an explanation. Ask to see the documents. Attend public meetings. And above all, support legislative efforts to make government more transparent. It’s too easy for officials who have failed us to point fingers, blame the media and wait for their side of the partisan fence to rally to their defense. We deserve better. We all pay taxes to support the work of government. We should get our money’s worth. |

Please note: Previous Sunshine Week content is still available for download and use.

Click here to access the eight newspaper in education features created for 2012 (3 column x 8 inches) - an overview of NYS FOIL, Open Meetings, How to gain access to records and one freature on Freedom of Information and NYS Courts.

Click here to access the five-part series of features highlights just a few of the websites with reports and other data that may be of interest to students and the general public. Graphic organizers to accompany these features are also available here as PDF download. The topics included:

• What is “E-Government”? – A brief summary of our “Cyber Sunshine” focus

• Vehicle Safety – Highway Safety Data

• Food Safety – Restaurant Inspection Reports

• School Safety – Violence and Disruptive Incident Report

Finally, click here to access five public service announcements in PDF format (2 columns x 6 inches) that can be use to promote Sunshine Week

If you'd like to make a donation to the NYNPA Newspaper In Education program, simply press the Donation button below.

New York News Publishers Association, Inc.

Phone/Fax (518) 449-1667 - Toll-free: (800) 777-1667